Fiction is one of the peculiarities of humanity. Unlike other species, Homo Sapiens began to imagine myths, entities and legends that he transmitted through time. It is these stories that allowed him to group together in larger and larger communities, where individuals were no longer bound intimately, but by these common beliefs. The prehistoric paintings on the walls of the caves are traces of the stories of these first Men. If they do not really put in situation the animals often represented, they sometimes tell a hunt, by sagaies sometimes piercing the sides of the beast.

The absence of archaeological traces does not allow us to evaluate the place that fiction really occupied in their lives, these stories being transmitted mainly orally. But the invention of writing, marking the passage from prehistory to history, brings us more evidence. If there are still many unsolved mysteries, we have knowledge of stories told then.

Whether mythological stories or codes of societies of the time, these writings have undoubtedly allowed the advent of the first great empires, based on these common beliefs. Beliefs telling the life and adventures of entities that do not physically exist in the real world. Yes, the big luminous ball in the sky exists, it is visible as long as the day lasts, but we have no proof of the existence of the gods Ra, Apollo, Sól or Huitzilopochtli. Thus, Man invented explanations for what he did not understand, for what surrounded him, for what he saw. And, around these inventions, he built durable societies.

Whether mythological stories or codes of societies of the time, these writings have undoubtedly allowed the advent of the first great empires, based on these common beliefs. Beliefs telling the life and adventures of entities that do not physically exist in the real world. Yes, the big luminous ball in the sky exists, it is visible as long as the day lasts, but we have no proof of the existence of the gods Ra, Apollo, Sól or Huitzilopochtli. Thus, Man invented explanations for what he did not understand, for what surrounded him, for what he saw. And, around these inventions, he built durable societies.

And Man has not stopped telling stories. Every human society has common myths. They are not necessarily religious myths, of the Creation or of what happens after death. What we call “classics” in movies, literature or even video games are also part of this common culture of society. Stories are at the heart of civilizations. And, if telling stories is not difficult, convincing others to believe them is much more difficult. How do you make them believable? Better yet, how do you make your audience feel emotions? How to make them feel involved in the story that is being told?

The forms of narration have evolved in this sense, seeking to impact the reader, the player or the spectator more and more. Nowadays, interactive forms of narration are the ones that are in vogue. What are they? What forms do they take? What are the challenges? Let me tell you about interactive narration, a crossroads between cinema, video games and literature.

The first media that come to mind when we talk about narration or fiction are books or movies (in the broadest sense of the term, as much movies as series or cartoons). We can also add video games, where narration is becoming more and more important, depending on the genre. It is interesting to notice the differences of each of these supports, but also their similarities. Let’s proceed in chronological order. Literature, the 5th art according to the classification of arts, appeared at the dawn of humanity as we know it. Because of its format, it presents mostly a linear narration (we will come back to the “mostly” later).

The story is constructed by the author, who delivers it to the reader as is. The reader has no impact on it, he is only a spectator. The choice of words, very important, will allow him/her to get attached to the protagonists, to devour each chapter (at the cost of his/her nights sometimes), and, above all, to feel the emotions and messages that the writer wanted to convey. However, contrary to what one might think at first glance, the reader is not completely passive in front of the story that is told. If we exclude the books for children, the majority of these works of fictions are devoid of images (except for the cover). Thus, the reader must constitute himself the visuals. He then imagines his own characters according to the descriptions which are made to him, the places which he crosses, the actions which take place… In short, he makes his own film starting from the words which he browses. Therefore, it is more than likely that there are as many representations of these stories as there are readers.

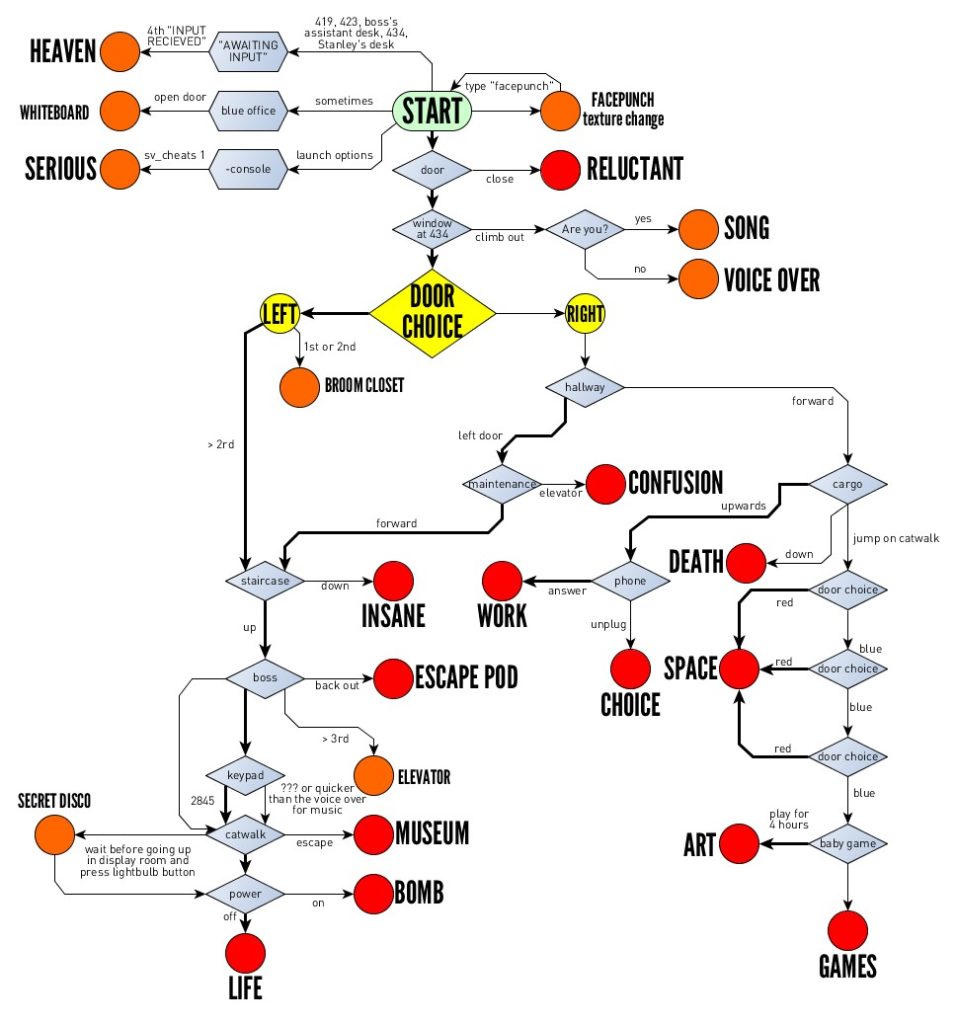

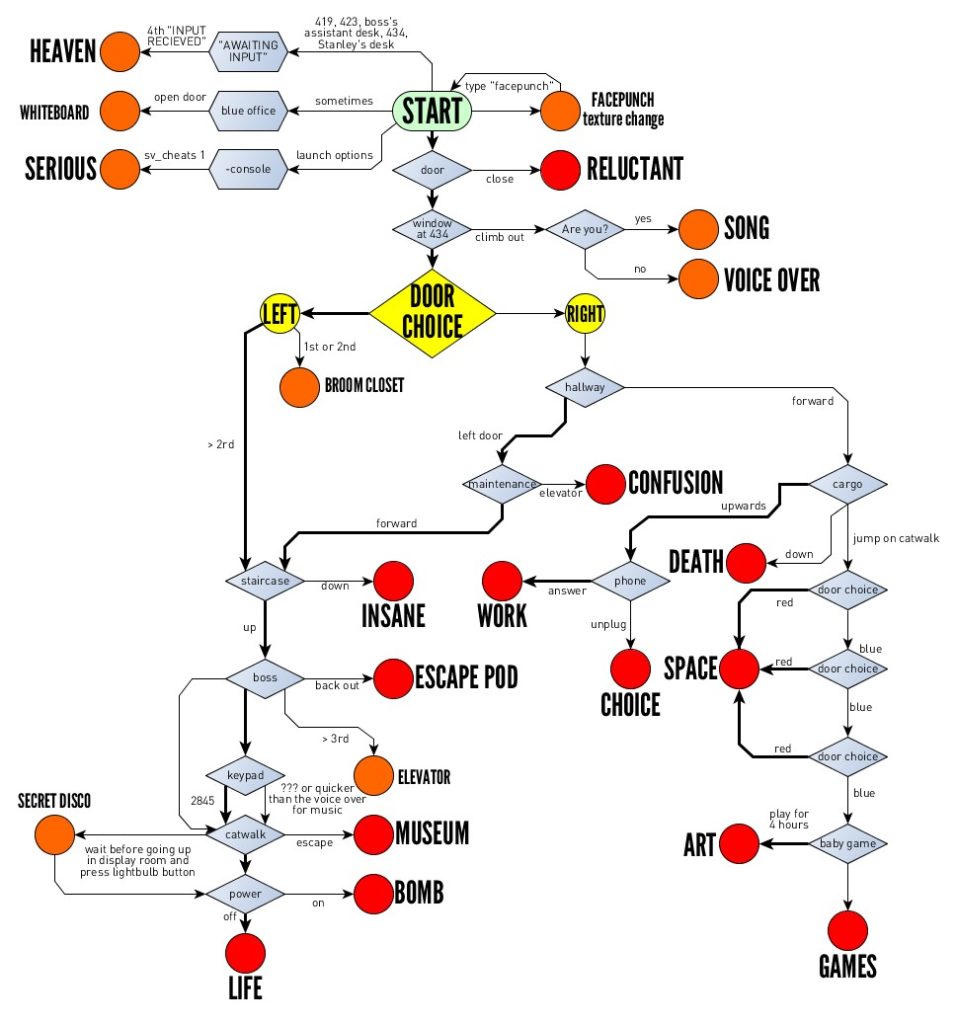

It is still possible to increase these differences between each person by changing a small parameter in the above. A small parameter not so insignificant as that: the linearity of the story. Indeed, although it is impossible to obtain total freedom, offering choices to the reader is feasible, and has been for a long time. It was in the 1960s and 1970s that the “gamebook” was born. You may know them as “books in which you are the hero”. For those of you who have never had the opportunity to try this experience, you are the hero books are like stories with choices, a bit like a video game or a role playing game.

The reader creates a character, much more succinctly than in a role-playing game (no, you won’t spend four hours customizing your avatar, much less a week memorizing the story for your next game). He then progresses through the story, sometimes picking up items that might be useful later, occasionally fighting brigands or other monsters, or picking up a clue from a merchant along the way. Then, the story stops. Pause. It’s time to make a choice. Left or right? Attack that man sleeping on the side of the road or wake him up to ask for directions? Or maybe even just continue on your way without paying him any attention? Hide in the ruined barn, or face the wolves?

Each fork in the road offers the reader a definite number of equally definite choices. And each choice is accompanied by the small statement “If you [insert choice], go to [insert number]”, referring the reader to a given paragraph to continue the story. There is no need to be afraid of turning pages here, forwards and backwards. Thus, from a simple book with a single scenario organized in a precise way by the author, you find yourself with an interactive story in your hands with several possible endings according to your choices. You are no longer a semi-passive spectator just imagining what is being told to you, but an actor in the success or failure of your story.

Speaking of actors, how about moving forward in time a bit? Let’s move on to the 7th art, cinema. Once again, the format induces a linear narration, even if it is said that there are 3 writings in a film: that of the scriptwriter, that of the director, and finally, that of the editor. Here, if the choice of words remains important for the spectator to take the characters seriously, the performance of the actors and the sequence of the shots also play an essential role in the capacity that the public will have to get attached to the characters. Perhaps you know someone in your circle (or you yourself are that person) who can’t stand a movie because they don’t like a particular actor?

Unlike books, the images are chosen by the production team, imposed on the viewer. Of course, the imagination is not necessarily entirely at half-mast, there may be elements suggested off-screen, which it will be up to each one to imagine, or not. But this activity of the public is, in my opinion, much weaker than for a book. One hears about films, often with a secondary scenario, where one could “put one’s brain aside” and simply let the images scroll. It is something more complicated to do in literature, since the reader already makes the “effort” to read.

Cinema, less interactive than literature? In this sense, it seems possible. But this is without counting the interactions that it provokes outside the viewing of the film itself. There are countless reviews of the latest blockbuster on YouTube before, during and after its theatrical release, and talking about the latest series you’ve seen on your favorite streaming platform is often a good way to liven up a conversation between friends. In this day and age where reading seems to be increasingly rare, interaction around movies is undeniably more important. It’s not a question of direct interaction with the work, but of interactions around it, all equally interesting. And what about the latest one?

Recognized as an art form since 2006 in France, which is not so recent anymore, video games have come a long way since the famous Pong, especially in terms of narration. Gone are the scenes that follow one another without any link between them other than a graphic coherence, gone are the princesses saved by a knight in shining armor. Nowadays, it is not uncommon to face complex stories, whether they are linear or with branches. In essence, video games are interactive. The player is the actor, he is the player, as the name cleverly (or not so cleverly) suggests. Yes, Pong is interactive. But what about the narrative? A key point not to be overlooked in this case is the player’s activity. Because of this involvement, it can be easier to make the player identify with the character he/she is playing and, by doing so, to make him/her feel emotions. So how do you write these stories, where you have to take into account that the player is one of the protagonists, and not a simple spectator?

Nicolas Pelloille-Oudart explains in the Nouvelles Narrations podcast, “A movie, a video game or… both?”, that storytelling is something quite recent in this field. You have to think of your story, if not interactively, so that the player is involved. He will rarely be the omniscient narrator of the story. They will rarely know what the other characters are thinking. He will rarely have insight into what they are doing when he is not with them. And yet they evolve too, in parallel. An additional difficulty can be added by getting closer to the Books of which you are the hero. What if… the player could change the story being told? What if there wasn’t some kind of hand of fate that had planned everything in advance, to the detriment of the dozens of hours spent in the universe he explores? What if he wasn’t obliged to follow this unique path thought out to the millimeter by the creators of his game? What if he wasn’t playing a game, but exploring a world? What if the player was in fact a person integrated into this world, able to influence it? The narrative can then no longer be linear, impossible. It explodes in tens, hundreds, thousands of branches composing each important choice of the player in order to, let’s be crazy, lead him to different possible ends. No more binary “Game over” or “You saved the princess, you win a kiss on the cheek” (yes Mario, we see you!). There are 93 possible endings in Undertale! Yes, the average is actually around ten or less major endings, with a few exceptions.

How difficult is it, in terms of design, to increase the player’s freedom? In addition to these choices, always more numerous, which can change sometimes a small element in the story, we move away more and more from the models of the platform games for a world more and more open… which will have to be alive. Because, it’s all very well to let the player walk around where he wants, if it’s to see nothing and do nothing except in the path predefined by the story, what’s the point? So how to “furnish”? By adding NPCs (Non-Player Characters) who can give side quests, tell their adventures, live their lives… and thus have their own story. There are often hundreds of characters created in this way. All this so that, potentially, the player will never be confronted with these lines of dialogue or these stories because he will not have explored this particular village in the north-west of the wooded area of the continent. This is the opposite of movies or “classic” books, where everything that is created and shown has a purpose: the creator doesn’t know if the player will even catch a glimpse of that character whose story he likes so much. But it is this abundance of small details that makes the success of a living universe that will last in time and beyond the borders of the game itself… or not.